I just returned from a writing conference where I heard a commonly held but very wrong belief among aspiring authors: “Don’t worry about genre. Your literary agent will help you identify that.”

While an agent may help you to identify subgenres and affinity groups for marketing purposes, you must know the genre or blend of genres your story will fall under before you start writing your book.

Different genres have different conventions. In a mystery, for example, the sleuth must follow the clues, solve the crime, confront the perpetrator, and lay out how they solved the puzzle. If another character solves the crime, the story won’t satisfy readers of that genre.

Sherlock Holmes solves the puzzles, not Dr. Watson. The protagonist and antagonist drive the story with their moves and counter moves. The plot (action) moves toward a clear and logical outcome.

Tropes are literary devices tied to plot. While some tropes are universal, each genre tends to have its own.

Ghosts or ghostly illusions, poverty, and religious zeal are a few of the tropes commonly seen in Southern Gothic literature (grit lit). And, as you might expect, the setting of Southern Gothic stories is in what we Americans call “the South,” a specific region of the United States with a long and complex history.

Wiley Cash’s A Land More Kind than Home, Karen Russell’s Swamplandia!, and George Saunder’s CivilWarLand in Bad Decline wouldn’t be what they are if they were set in Wisconsin or Nevada. The geography, history, and culture define the characters’ worldview and positions in society and dictate what events/actions (plot points) are or are not reasonable or possible.

Many writers will defend their nonconformity by claiming artist status and a disdain for “formulaic writing.”

That’s nonsense. We don’t accuse chefs of French, Indian, Mexican, Thai or any other specific culinary style of being formulaic for using regional bases, spices, fruits, and vegetables. In fact, we’d likely be confused and disappointed if our enchilada came out smothered in coconut milk rather than mole or a tomato-based sauce.

Likewise, think of tropes as ingredients. Not every French dish will contain all of the ingredients within the scope of that cuisine, but there are things you’d expect and things you’d be dismayed by. For example, snails would be acceptable but a crispy scorpion would not.

New writers who haven’t considered genre upfront and defined the scope and chosen the tropes of their story accordingly, often default to the less plot driven and trope-y genre of literary fiction or will say that their story is upmarket.

While literary fiction tends to be more character driven and less dependent upon genre conventions, it is not a catch-all genre. What distinguishes literary fiction from other genres is its exquisite prose and intellectual bent.

These are the books that, though not typically widely read, win literary awards. For example, far more people read books by Stephen King than Anthony Doerr. Both are excellent but serve different audiences at different times.

What’s important to remember about upmarket fiction is that it is not a genre but a description. Upmarket fiction contains elements of several genres and artfully crafted sentences and well-developed metaphors. Equal attention is paid to character development and plot.

Colson Whitehead’s The Underground Railroad is an excellent example. It’s a Pulitzer Prize winner that has elements of literary, historical, and magical realism genres. It has the strong character arc and beautiful prose we expect from literary fiction and the life or death stakes and gripping plot we expect from other genre fiction.

Delia Owen’s Where the Crawdads Sing is another example of upmarket fiction. There is a mystery, but it’s not executed in the classic mystery genre convention. There are elements of Southern Gothic—setting and poverty, for example—but no ghosts or religious fervor. While the author crosses genres, it’s obvious that, like a master fusion chef, she selected each ingredient purposefully for a specific effect.

Professionally minded authors craft their books. They start with the end in mind, understand the market, and know their audience’s tastes. They carefully select and measure ingredients for maximum flavor and effect.

Amateurs reach for and incorporate whatever sounds good at the time without considering how each ingredient complements or competes with the others. They shift the responsibility for labeling the menu item to others and often cannot clearly articulate the value or essence of their own creations.

Professionals do not blame the servers or diners if a dish fails to sell or meal fails to please. They look to themselves, to their kitchens, and to their processes and actively develop the knowledge and skills necessary to succeed. We must love what we do. But for professionally minded authors, at the end of the day, we write to feed our readers. It is their craving we satisfy, not our own. What is ours is the unique way we use familiar ingredients to surprise and delight consumers.

When I hear people say that they’ll worry about genre later, I know they have failed at the premise. And, as a lover of books and their creators and having an appreciation for the tremendous amount of effort writing a book takes, it makes me sad.

At least with a book, unlike a soup or most dishes, it is possible—with tremendous effort—to deconstruct and reconstruct a story (assuming the author is willing to get and apply professional feedback). But why frustrate ourselves and willfully increase the chances of serving our readers something they are likely to want to send back to the kitchen?

Who Is Your Ideal Reader, and Why Does Your Book Matter to Them?

To Write a Better Memoir or Novel, Think Like a Screenwriter, Movie Director, and Cinematographer

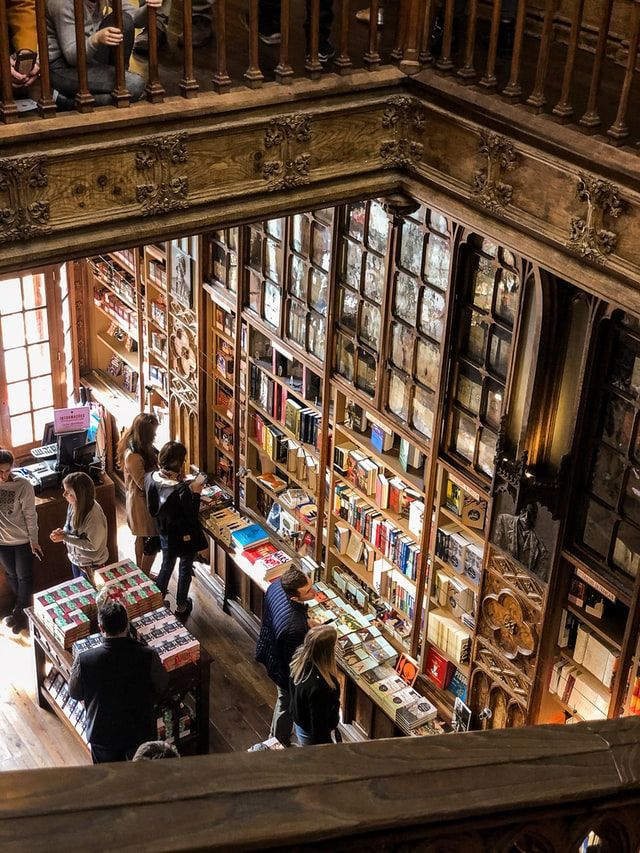

Photo by Square Lab on Unsplash

CI Communication Strategies

2019